Recent Presentations and Articles

15 Participatory Research, Popular Education, and Action for Social Change

Jose Zapata Calderon

https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197615317.013.16

Pages: 303–314

Published:19 September 2024

Abstract

This chapter is based on the involvement of a longtime scholar-activist reflecting on the use of popular education and participatory research in his development. The use of these pedagogies and methods, dating back to social movements in the Global South and North, have been used with a vision of transforming the unjust power relations of colonialism, patriarchy, and capitalism while creating new models that involve the participants in research and action to create radical systemic change. The author presents examples from his history of teaching, research, and organizing on how these methods have been applied and how they can be used in the contemporary period.

Keywords: participatory research, popular education, social movement, systemic change model, community-based organizing

Subject

Political SociologySociology

Series

Oxford Handbooks

Collection: Oxford Handbooks Online

I have had a life of experimenting with how one connects research, teaching, and learning with social change organizing. In this process, I examined the differences between concepts of charity, project, and social change, like issues raised by Keith Morton (1995) in his article “The Irony of Service: Charity, Project, and Social Change.” Morton exposed the charity model’s disempowering potential to make recipients dependent on providers’ services. At the same time, he argues that, though the project model sometimes offers solutions to immediate problems, it often leaves the planning, analysis, and action in the hands of experts. Such projects rarely build the capacity or open democratic opportunities for community partners so they might gain the necessary power to change the root causes of social problems.

My community-engaged scholarship draws lessons from a type of community activism that collaborates with communities and acts on concrete issues. This approach falls within the social change model that Morton defines as a type of organizing and pedagogical practice seeking to challenge the systemic roots of oppression by “politically empower[ing] the powerless” (Morton, 1995: 23). These practices form a kind of sociology steeped in community-based action and engaged research openly committed to the creation of democratic places and spaces as well as a broader movement for social justice.

Some of the early literature on the field of participatory action research (PAR) gave credit to scholars such as Kurt Lewin and William Foote Whyte for developing engaged research within the academy. However, these early works represented more of a top-down traditional research model with little involvement by the people being studied in the design and analysis process. Recently, scholar-activists argued for a more radical PAR model found in the historical works of the settlement house movement led by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr as well as from the Highlander Research and Education Center Directed by Myles and Zilphia Horton in Tennessee (Strand et al., 2003: 5–8). Considering my own historical development as an activist researcher and PAR practitioner, I find it necessary to also bring to center stage the work of engaged teaching and research from Latin America. Most notable was the popular education methodology implemented by Paulo Freire. In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, he eloquently describes the evolution of his approach as he developed a methodology to teach literacy in Brazil. He focused on ways to encourage participants’ own reflections on their history, on their conditions, on power relations, and on other local systems in their lives, moving their group from critical reflection to action (Freire, 1993).

In the 1970s, this kind of participatory research differentiated itself from traditional social research by involving the participants in both the research and action to create radical systemic change. Today, this liberatory social change approach is still used but more in terms of creating models of spaces or places that exemplify a more just and equitable society. Orlando Fals-Borda, a Colombian sociologist, embraced social justice–oriented work by combining popular education with community-based research. His collective and collaborative efforts developed training workshops, produced interviews and ethnography, and created graphic historical texts using testimonies from the people. His goals included empowering peasants by interpreting and understanding their past to create a new future together. A key aspect of this “people’s science” and “critical recovery” methodology creates opportunities for dialogue and knowledge production where community participants are equal; where the researcher and the researched are interconnected; and where the results of the research are important in turning around unequal power relations (Rappaport, 2020). In many ways my own theoretical and scholarly development has similarly avoided a separation between my research interests and my activist history. My experiences fit in with the kind of intellectual activism that Patricia Hill Collins proposes, where links are made between “content and process, ideas and actions, and oppression and resistance” (Collins, 2013: xv, xvi).

Today, as right-wing conservative movements promote the concentration of wealth as a plan to advance unequal growth, more than ever before we need to advance popular education and research while developing alternative strategies and practices. Activist scholars must engage with our communities to understand and tell stories about how histories of unequal and systemic stratification have divided our national and global communities based on wages, wealth, identity, and opportunity. Promoting race-blind interventions, as we know, does nothing to dismantle racism’s legacy of incarceration, segregated housing patterns, and discrimination in access to resources such as healthcare and education. These conditions require activist scholars to connect theory with practice through transformative collective action and community sharing of knowledge. Such strategies link theory and practice to deploy social analysis and political reflection that turn collaborative experience and ideas into visions of alternative systems based on the radical resistance it took to get there.

A Student of the 60s

I was first drawn to such theories of praxis as an undergraduate at the University of Colorado (UC) in the late 1960s. Faculty introduced us to the work of Paulo Freire and the notion of engaged scholarship embedded in political liberation movements. At UC, I met students such as Ricardo Falcon and Freddie Trujillo (among others), who inspired me to confront who I was and what role I could play in fighting for increased Chicano and Chicana admissions on campus. They also influenced me to confront the racist policies of Joe Coors (the owner of the Coors Beer Company who sat on the University of Colorado Board of Regents at the time and voted against any programs that would increase the school’s non-White student body). We exposed how few students of color attended UC by juxtaposing the racial statistics on campus with the disproportionate number of Chicanos/as and Black people—as opposed to White people—killed on the front lines in Vietnam. As a student body vice-president, I helped lead a strike that shut down UC over the murder of students at Kent State and Jackson State, again linking those incidents to racial discrimination in campus enrollments. In response to the strike, we opened a new, parallel yet alternative university. These protests were my first experiences in seeing how popular education could be used as a tool for building spaces and places that collaborated with our communities, accepted their issues as the focus of our efforts, and advanced a vision of the kind of world that we all have a right to live in.

At that time, I learned about a conference being held in April 1969 where students, teachers, and other activists had organized a nationwide conversation. Their goal focused on bringing diverse student groups together under “El Plan de Santa Barbara.” This document unveiled the fight for community-based recruitment, curriculum changes, and building Chicano/Chicana Studies programs and departments at UC schools. The group’s premise claimed that Chicano and Chicana Studies should serve the interests of Chicano/a communities—and that students and faculty should work, study, and research alongside communities, collectively addressing the issues they faced. Together we could fight for solutions to these conditions.

This history explains the importance of bringing to center stage the development of community-based research, teaching, and action that originated in our Chicano and Chicana communities. Examples of scholar activists, such as Ernesto Galarza, Betita Martinez, and so many others captured the imagination and the heart of students like me who had come out of barrios. But we were also inspired and influenced by the larger Chicano and Chicana movements and the civil rights movement in general. These opportunities developed from such organizations as the United Mexican American Students and Movimiento Estudiantil Chicana/o de Aztlan (MECHA), which used popular education to organize and empower our communities. Not only did we protest the war in Vietnam but also we exposed the reality that our young people were being drafted and jailed disproportionately, at the same time they were pushed out of schools and left out of higher education.

The 1969 conference, coming on the heels of a growing movement for land, language, cultural, and human rights gave birth to various other organizations such as the Mexican American Youth Organization in San Antonio, Texas, in 1967—a group that later became La Raza Unida Party. Similarly, the Brown Berets, who organized against police violence in East Los Angeles, joined with the United Mexican American Students (UMAS), Sal Castro, and young people throughout the community to organize the East LA school walkouts protesting push-out rates and the maltreatment of Chicano students in the LA school system. These increasingly militant collaborations led to another April 1969 gathering, this time organized by the Colorado-based Crusade for Justice. Participants included many Mexican American student groups, including MECHA, who together adopted “El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan,” which called for the self-determination of our Chicano/a communities.

The event gave birth to a diverse student coalition initially called the Chicano Coordinating Committee on Higher Education (CCCHE) but eventually known as the “Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán.” Out of this conference, with the passage of El Plan de Santa Barbara, grew a national movement, with MECHA in the lead. They organized pressure for Chicano/a studies programs linked to community struggles and focused on recruiting Chicana/o students, building engaged curricula, and expanding resources for Chicano/a Studies programs and departments. Again, the growing outlook then was that Chicano and Chicana Studies should serve the interests of our communities and that our students and faculty should be alongside our communities in collectively understanding issues and fighting for solutions to their conditions.

The kind of organizing that we did at that time had an inside/outside character: by working inside higher education to pass policies supporting people of color, stopping the war in Vietnam, and through combining these efforts with supporting striking farmworkers and the grape boycotts taking place throughout the country, we were able to make institutional changes that then supported political movements. These movements, both local and national, developed new student and educational activists in our schools, universities, and communities. It is this kind of “dual location” that Patricia Hill Collins (2013) describes in her book On Intellectual Activism in terms of being an insider and outsider.

I was part of a student government that took the vote of 10,000 students to shut down the UC campus. But we created popular education activities to open a new university hoping to use institutional resources to travel around the state and educate communities about why students were against the war and how US imperialism and colonialism linked to other local and regional issues. One of the billboards that we designed included the dead body of a young soldier with the caption: “Dear Mom and Dad, Your Silence is killing me in Vietnam.” These efforts led students like me to make connections between and among the different movements. Hence, when Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta came out calling for bathrooms for agricultural workers in the fields, the labor movement struck home as I remembered my mother working in the fields. Our evolving consciousness continued to inform our analysis, especially when we learned that the Nixon administration’s Department of Defense had bought massive amounts of grapes and sent them to Vietnam. Many of us who were organizers on campus made these connections and asked, “What kind of justice is this?” Some, like Magdaleno Avila (who led a lettuce strike of farmworkers in southern Colorado), became role models when they returned to their communities to organize.

From Student to Community Organizer

In my case, influenced by the acts of such individuals, I caught a bus to Delano, California, to experience the farmworkers’ struggle. The farmworkers’ union employed popular education but also infused other aspects of culture and spirituality as they conducted pilgrimage marches, fasts, and picket lines for their cause. At the same time, they created spaces and places that exemplified solidarity and collectivity. Farmworkers developed cooperatives and made sure everyone received decent wages and working conditions. For some of us, this connection made sense and, in my case, led to reading about Camilo Torres, Orlando Fals-Borda, and the use of participatory research and “people’s knowledge” alongside campesina leaders such as Juana Julia Guzman.

I returned to my hometown with the outlook of sacrifice, not putting value on material things but using my life as part of the struggle. I took an old garage in my parents’ backyard, painted it red with a huelga eagle, and started popular education efforts to work with young children, teaching them English. The effort was so successful that the parents organized and went to the school board to ask for bilingual education. The school board told them to go back to Mexico. In response, our young students and parents marched from Ault to Denver (the state capital) and built a movement. Some of these same parents also took up a struggle to close a local feed lot operation in the barrio. As part of the organizing, young people, their parents, and I conducted research that showed how the feedlot was improperly located inside the city limits and should be closed. This type of research was not based on publishing but on creating a better living environment for our barrio residents on the east side of the tracks.

Working from, and being embedded in, the everyday grassroots lives of people, knowledge produced in these struggles is not elite and exclusive, but instead forms a powerful model of “the people’s knowledge.” This approach results in data and analysis that serves political struggle itself. We developed knowledge in the course of struggle as both analysis and weapon of struggle. This approach connects theory to practice through transformative collective action, not only as a way of acting in struggle but also as a collective method of creating new visions of, and experiences with, alternative systems of human relationship and human life.

The significance of this period was that we began to look at the structural foundations, not just the immediate struggles. We built and worked in organizations that introduced us to international examples where people experimented with creating new economic systems. The movement featured efforts to connect the spirituality (the solidarity and communing together) of justice spaces and places to concrete examples—echoing Freire’s strategy of popular education and Fals-Borda’s PAR. The key aspect of these methodologies rests on the creation of dialogue where the community participants are equal, where the researcher and the researched are interconnected, and where the results of the research empower people to turn around unequal power relations. In these early examples of using popular education, organizing, and participatory research, what was important were the outcomes created by collective organizing alongside community participants that, by focusing on the structural changes needed, created a long-term commitment.

Sociology for Social Justice: A Hybrid Life

Today, in the academic world, faculty and administrators still lack an understanding about the meaning of popular education, teaching and learning, and participatory research in general. If we engage in the research process as activists, traditional scholars and gatekeepers for rewards and tenure often criticize us as not being “academic” enough and that our research lacks “rigor.” In a recent article for the Urban Education journal, I coauthored a piece with Mark Warren and others where we asked the question: “Is Collaboration-Engaged Scholarship More Rigorous than Traditional Research?” Here we argue that the highest level of community-engaged scholarship is one where the scholar collaborates with community participants in diagnosing and defining the problem, in analyzing the outcomes of the research, and in using the research to present and implement solutions (all aspects of participatory action research). These activities include a practice where, rather than “expert” solutions being predefined, the results of the research are interpreted and used as guides for action and advancing social change (Calderon et al., 2018: 4–5). In response to critiques by traditional researchers that this kind of scholarship is “not science” and “not rigorous” because one is involved both as a researcher and an activist, we argue vehemently that “no research is purely objective; no researchers in the world, even in the hard sciences, can separate values and personal standpoints from the intellectual or scholarly enterprise.” On this point, no researcher can avoid bringing underlying assumptions to their work, and these inescapably shape the questions asked, the data considered relevant, and the methods used. The real issue is not whether collaborative community-based research is rigorous or not, but about how rigor itself is defined. All scholars, activists or not, begin rigorous research with the basic principles that we should use appropriate and systematic methods; that our work must stand up to critique by knowledgeable parties; and that we consider contrary evidence and alternative hypotheses. But “rigor,” we know, is often used as a code word for a set of practices that align themselves with detached rather than engaged research. And this detached process—usually referred to as “objective”—is often corporate- or grant-funded and serves the elite and hegemonic status quo. This collaboration seems the furthest thing from objective.

As I move from an academic or theoretical answer to this critique of PAR to the power of community-based research and action itself, I return to the propositions of Ira Shor and Paulo Freire, in their book A Pedagogy for Liberation. Here they argue that the traditional meaning of “rigor” needs to be redefined. They call for a “creative rigor” that critiques the authoritarian way of transferring knowledge, which mechanically structures education—and discourages us from the responsibility of recreating ourselves in society” (Shor & Freire, 1987: 77). Thus, Shor and Freire also propose a “creative pedagogy which seeks to reinvent knowledge situated in the themes, needs, and language of communities as an act of illuminating power in the society” (Shor & Freire, 1987: 81). In this context, I argue that this type of community-based research and engagement can be more rigorous because it is accountable to input and critique beyond the narrow circles of academia to include the experiences and perspectives of the communities we engage with. This real-world accountability differs markedly from most types of traditional, detached academic research where responsibilities are either to private donors, elite foundations, or simply the career trajectory of individual researchers themselves. From this point of view, collaborative community-based research and engagement demonstrate a richer and more complex rigor because it must demonstrate its credibility to a broader audience, with accountability to community partners, and to the demands of actual engagement and practice, and with solid outcomes in the interests of our communities in the end.

Over the years, I have been part of movements steadfast in defending the rights of our communities to contest current and local issues within the context of a larger historical battle with colonialism. The resulting practice includes an analysis of how the practices of settler colonialism have influenced the structures and systems that inform contemporary inequalities and injustices—in the communities and in the universities. The current conditions of our communities are not separated from this country’s practice of colonization and of a system of capital that historically exploits our labor and our resources (here and abroad) to serve the interests of international capital and multinational corporations. Along the way, we have never wavered from an analysis that the families who come here from Central America, Mexico, Haiti, Africa, Asia, and Latin America are coming because of this country’s foreign policies that have exacerbated violence and inequality (with such trade agreements such as NAFTA), have uprooted farmers and peasants, and have subsidized multinational corporate interests. These unjust policies, which have historically separated immigrants into political and economic refugees, were founded on the political and economic relationships between the United States and their colonies—regardless of whether colonies supported US power or not. True rigor must embrace the inherent ties between the local and the global, the personal and the social, the problems of today with the foundations of these historical oppressions.

The Future of Our Engagements

With movements emerging, such as Black Lives Matter and those resisting the scapegoating of our ethnic and immigrant communities (Latino and Asian Pacific Islanders in particular), there is the need—more than ever—to advance a type of popular education and participatory research based on creating systemic change alternatives. Accomplishing this goal does assume that movements can use our research, pedagogy, and engagement to expose and oppose such contemporary social problems: the school to prison pipeline; unjust detention centers; voter suppression laws; and acts of cultural, political, and outright physical genocide that try to keep our communities from organizing and mobilizing for political power. But we need to move our own engaged pedagogy and research directly toward building such movements. Activist and engaged researchers need to embrace emerging movements throughout the country to build cooperative models of democratizing wealth and community-based economic alternatives focused on the collective welfare of the many and not for private interests or profit for a few. In my view, the farmworkers union is an example of an organization that sustained itself in the early years using credit unions, cooperative gas stations, health clinics, and places like the Filipino Hall cafeteria. Now, alongside unionization efforts in the fields, they use land cooperatives, radio stations, low-income farmworker and elderly housing, and “huelga” stores as a means of sustaining itself and its members.

In this context, there is a new movement of engagement emerging in the United States committed to creating new structures based on democratizing wealth. These efforts drive collective enterprises and new models of economic development with racial justice in the forefront. These projects include worker-owned cooperatives, credit unions, agricultural cooperatives, consumer cooperatives, and employee-owned companies, all of whom collectively represent $500 billion in revenue and employ more than 2 million people.

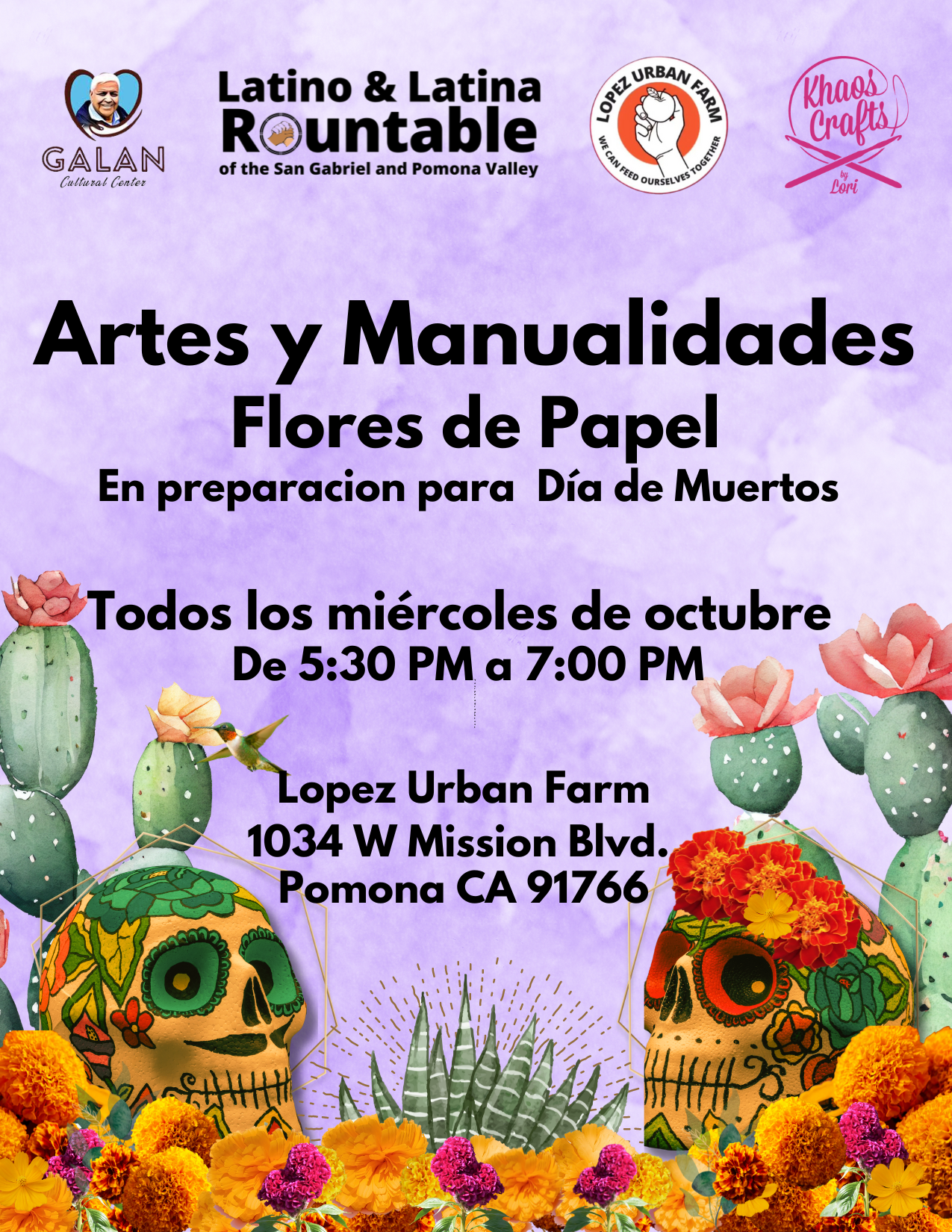

Community- and activist-based researchers support such efforts as part of our growing network of solidarity and social justice. In California, we have examples such as the National Day Labor Organizing Network, which uses participatory research and popular education in organizing immigrant workers, in implementing educational leadership schools, and in developing their own radio station with day laborer radio announcers (NDLON Popular Education Program, 2022). We work in partnership with the Huerta del Valle community garden (a 4.5-acre community garden in Ontario, California, led by Maria Alonso and 61 primarily immigrant families) and other community-based urban farms in advancing the use of the land in saving the environment and in building organizations which prioritize the use of our resources (including our tax dollars) on quality of life development (Huerta del Valle Comunitario, 2022). We have also been a part of the Latino and Latina Roundtable that connects local and statewide organizing by holding monthly meetings, participating in local legislative trainings, and conducting an annual Advocacy Week in support of educational legislation to support education. These actions, in partnership with the statewide College for All coalition, have resulted in numerous successes including $250 million for college readiness and $540 million to ensure that schools implement A-G courses required for admission to California public universities (particularly for low-income, English learners, and foster youth). The implementation of popular education methods has included workshops, forums, and seminars with parents, students, teachers, and “anchor” college representatives on topics ranging from the Educational Justice Movement to implementing an Ethnic Studies requirement, to the implementation of the concept of community schools. We believe that community schools may be a crucial tool for developing participatory democracy and the necessary solidarity to find solutions for some of the key problems.

Our local support also comes from a long history of leading immigrant rights efforts in the region and ongoing supportive efforts of unions. In December of 2003, the Latino and Latina Roundtable (LRT) led a march through 22 cities (from Our Lady of Assumption Church in Claremont to Los Angeles) to protest Governor Schwarzenegger’s doing away with a bill that would have given undocumented immigrants the right to a driver’s license. In June 2004, as part of a larger Inland Empire coalition, the LRT led a march of 10,000 from Ontario to Pomona in protest of unjust immigration raids where over four hundred undocumented immigrants had been picked up (Vega, 2004). Over a 20-year period the LRT has been developed much like a cooperative with a membership base that pays dues and with committees that have developed a culture of “using their lives in service to community” through educational justice and immigrant rights issues throughout the region. The commitment of the members has been drawn through taking up issues in the community that have connected the educational and immigrant rights needs of families. These connections have included: the stopping of unjust checkpoints; supporting voting rights efforts that have ensured the implementation of district (and not at-large city elections); the implementation of workshops on how students can qualify for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, how to obtain a Matricula Consular card (an official identification document issued by the Mexican government), and how to obtain a California driver’s license.

The use of participatory research and action has played a role in the organizing of workers at Pomona College and Pitzer College, where workers, with the support of the UNITE-HERE union, students, and community-based organizations such as the LRT, have voted to unionize and are now negotiating for better benefits and wages. The research revealed that although Pomona College has a $3.03 billion endowment, making it the seventh-wealthiest college on a per student basis, the dining hall workers remained at the lowest levels of the stratification ladder.

As part of these efforts, in the city of Pomona, an LRT board member was elected to the city council. This councilperson, alongside a coalition of groups that includes the LRT, has spearheaded a proposal, supported unanimously by the city council to advance the implementation of a new economy proposal that includes working with community partners in engaging anchor institutions (colleges, hospitals, city governments, school districts, labor unions, local businesses) and Pomona residents in building support for the concept of “a well-being economy.” Working in a horizontal partnership with the community, we are also promoting the use of participatory action research to identify areas of need that can be met by local cooperatives that supply food, energy, and services; and that includes the construction of a detailed work plan for such cooperatives.

These efforts are already impacting statewide support as well. Governor Newsom, as part of a movement to establish a National Infrastructure Bank, recently signed a bill supporting the establishment of a state-operated public bank. Locally, representatives from the cities of LaVerne, Pomona, and Claremont have been meeting on the possibilities of developing a regional public bank with the outlook of all investments returning to our communities. In the city of Los Angeles, a report from the chief legislative analyst supports funding for the development of a municipal public bank. These activities rely on research exemplified by PolicyLink and scholars like Angela Blackwell, whose work advances organizing for policies to get the banking industry to close the wealth gap by providing free interest loans to Black-owned businesses and unleashing the creativity of Black entrepreneurship (Blackwell, 2020).

We are also exploring how to use innovative technologies to organize our communities and incorporate popular education and participatory research in these efforts. These areas represent new frontiers on how to employ modern technologies in tackling urban problems, fighting for principles of racial equity, designing transformative solutions, and involving our communities in their implementation. These explorations include: (1) thinking of new ways to democratize wealth; (2) placing the interests of our communities in the forefront in all development; (3) decentralizing power with the voice of our communities in the forefront; and (4) planning that prioritizes jobs, healthcare, education, and investment in our quality of life.

Overall, our organizing efforts today can ensure the original principles developed in our early movements, such as those of El Plan de Santa Barbara, in using our education, research, teaching, learning, and organizing as tools to collaborate horizontally with our communities to build alternative systemic examples to the sources of our historical oppression. The potential is there to influence systemic change on a large scale by using popular education and participatory research, not only in our community-based organizing in the community but also using the innovative technologies in promoting and creating alternative forms of ownership and new local and global transformative structural models of racial equity. If we include and encourage the communities we work with, we can advance the gains that our movements have made in challenging the undemocratic top-down models of decision-making and advance new transformative economic, social, and political models that can serve as bridges to a more just and equitable society.

Acknowledgments

This article was based on presentations made at the National Association for Chicano and Chicana Studies 50th Anniversary Conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico on April 22, 2022, and Part of “El Movimiento: The Chicano Movement in Northern Colorado” panel forum sponsored by the University of Northern Colorado’s Chicana/o and Latinx Studies program on September 22, 2021.

References

Blackwell, Angela Glover. “Banks Should Face History and Pay Reparations. ” New York Times. June 26, 2020.

Calderon, Jose, Mark R. Warren, Luke Kupscznk, Gregory Squires, and Celina Su. “Is Collaborative Community-Engaged Scholarship More Rigorous than Traditional Scholarship? On Advocacy, Bias, and Social Science Research.” Urban Education Journal 53, no. 4 (April, 2018): 4–5.

Collins, Patricia Hill. On Intellectual Activism. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2013.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum, 1993

Huerta del Valle Jardin Comunitario. (2022). https://www.huertadelvalle.org

Shor, Ira, and Paulo Freire. A Pedagogy for Liberation: Dialogues on Transforming Education. New York: Begin and Garvey, 1987

Morton, Keith. “The Irony of Service: Charity, Project, and Social Change in Service Learning.” Michigan Journal of Service Learning 2, no. 1 (Fall, 1995): 19–32.

NDLON Popular Education Program. “Popular Education Liberates: See, Think, and Take Action.” (2022). https://www.popedliberates.org

Rappaport, Joanne. Cowards Don’t Make History: Orlando Fals Borda and the Origins of Participatory Action Research. Durham; London: Duke University Press, 2020.

Strand, Kerry, Sam Marullo, Nick Cutforth, Randy Stoecker, and Patrick Donohue.

Community-Based Research and Higher Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003.

Vega, Miguel Angel. “Migrantes Reclaman Justicia.” La Opinion (June 14, 2004): 1.

Recommended

Spaces and places for popular education and participatory action research

Marjorie Mayo, Policy Press-5, 2020

Radicalising Community Development within Social Work through Popular Education—A Participatory Action Research Project

Peter Westoby, The British Journal of Social Work, 2019

Participatory action research and policy change

Brett G. Stoudt, Policy Press-5, 2015

Education and Research of University of Cambridge & Digitalization and Sustainable Education

Nicola S. Clayton, Frontiers of Digital Education, 2024

Popular congresses for 2023 – 2024

SA Heart, 2023

Parameterized Algorithmics for Computational Social Choice: Nine Research Challenges

Robert Bredereck, Tsinghua Science and Technology-1, 2014

Powered by

More from Oxford Academic

Political Sociology

Politics

Social Sciences

Sociology

Books

Journals

About Oxford Academic

Publish journals with us

University press partners

What we publish

New features

Authoring

Jose Zapata Calderon Emeritus Professor of Sociology and Chicano/a and Latino/a Studies 1050 North Mills Avenue Claremont, CA 91711-6101 (909) 952-1640 Jose_Calderon@pitzer.edu Website: www.josezcalderon.com

The Continued Need for Our Movements to Connect the Local and National with the International

by Jose Calderon Aug 2, 2023

It is important that any analysis of the electoral, labor, immigrant, and racial inequities in the U. S. include the relations between the local, national, and international. Of primary significance in that analysis must include the U. S. involvement in Ukraine, its policies toward China, and the results of those policies on the working class in the U. S. and the countries of the global south.

Biden’s policies are taking billions away from needed resources in the U. S. to expanding the war in Ukraine; to advancing militarization policies from Japan and South Korea in the northern Pacific to Australia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Singapore in the south and India and China – as part of policies aimed at encircling China and advancing support for an independent Taiwan. The Federal Reserve’s raising of interest rates has resulted in corporate profits being the biggest contributor to inflation. Many neoliberal economists and Western central bank officials have ignored the rise in corporate profits and instead have blamed inflation on workers’ wages. Today’s inflation and the use of economic sanctions throughout the world has caused the U. S. Dollar to continue its dominance, to becoming more expensive, to driving up costs, to deepening poverty conditions, causing food shortages (in the global south, Middle East, North Africa, and worldwide), and forcing increased migration from the South to the North. This soaring inflation and the devaluing of currencies have created a debt crisis in these regions resulting in their currencies depreciating, the U. S. dollar strengthening, and an inability for these countries being able to service their debts.

There is no getting around how the Ukraine war and the economic war with China is affecting many countries of the Global South that are principal trading partners and investors. Argentina, for example has an inflation rate that has reached 100%. As in the debt deal here in the U. S., the governments in the Global South, including eight countries in Latin America who are now led by left administrations, are having to cut health, education, and welfare programs. The result has been massive protests in these countries as well as looking for alternative solutions such as developing their own currencies and regional cooperations (such as the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) as an alternative to the Organization of American States (with a recent meeting where there were agreements on strengthening economic trade cooperation).

In following with the analysis that the families who are coming here from Central America, Mexico, Haiti, Africa, Asian, and Latin America are coming as a result of historical colonization and this country’s foreign policies (that have historically separated immigrants into political and economic refugees based on the relationship between the U. S. and whether it supports the government and policies of their country of origin) we have 450,000 refugees admitted legally to the U. S. in the last two years – and a double standard applied with 300,000 from Ukraine and with Afghanistan and Latin America accounting for the rest.

While the Biden administration has extended Temporary Protective Status for 670,000 immigrants from 16 countries (a program that Trump wanted to terminate) – and a (temporary – 2-year) parole program for up to 360,000 immigrants from Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, the administration has followed up its support of asylum bans similar to those implemented by Trump (such as Title 42 that was used to deport nearly 3 million asylum seekers) with another measure prohibiting immigrants and refugees from seeking asylum at the border without first applying for protection in a country they passed through (a measure blocked this week – by a federal judge in California). Meanwhile, three Republican governors are implementing a strategy, proposed by Trump back in 2018, to bus and fly thousands of immigrants from the border to sanctuary cities and places such as Martha’s Vineyard. The xenophobic strategy is now part of the election campaigns of right-wing politicians and candidates, including Trump, who are placing the immigration issue at the top of their agendas in criticizing the Biden administration for its “lax” immigration policies.

There is no getting around the existence of world capitalism and the economic wars that are going on and how they affect our internal politics and economics. There is a continued need to deepen our vision for systemic change, something that the social movements in the Global South are dealing with in overcoming the obstacles of international capitalism and neo-liberalism.

There is the need for a social movement that includes organizing for peace and channeling needed resources to climate change and quality of life – a movement that is able to cross borders and build alliances with movements in the Global South with strategies that are aimed at the same source that is fueling militarization, sanctions, encirclement, scapegoating and corporate profits at the expense of working people, a movement that organizes our communities against immigration and refugee policies that only focus on enforcement, that fights for policies that will lead to permanent residency and citizenship for our immigrant and refugee families, and that steps-up citizenship drives and voter turn-out efforts to expand the number of representatives who can advance systemic changes for our quality of life and for global pro-immigrant and non-exploitative development policies.

Affirmative Action Decision shows that Supreme Court is Not Neutral

The 6 to 3 decision by the Supreme Court rejecting affirmative action at colleges and universities brings to mind an article that I wrote awhile back whose arguments are still relevant today.

The decision comes at a time when there is an increasing trend of competition for resources with some students and conservative organizations claiming that there is “reverse” discrimination in the admissions policies of numerous colleges. The cases are also coming when there is increasing competition for limited local and federal education funds and when racial discrimination is being written off as though it did not exist anymore. Memory is short, and some critics have forgotten how segregation divided this country not too long ago.

Today, there are those who argue that affirmative action has resulted in the development of a growing middle class among underrepresented minorities. They also argue that such policies do not serve the needs of those who are stuck at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. What they fail to point out is how affirmative action has helped in opening the doors to social mobility for some of these same individuals now in the “middle class.”

Critics also argue that we need “class-based” solutions such as full employment, national health care and quality education that can pull everyone up simultaneously. What they fail to point out is how people of color, even if they reach middle-class status, confront unequal resources and a glass ceiling that prevents them from moving into managerial positions.

Critics are hiding behind the argument that we need to strive for a “color blind” society, arguing that affirmative action only serves to divide working people by allowing one group to benefit at the expense of another. This logic leaves out that specific groups, because of racism and sexism, have been historically excluded or left at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. It leaves out the historical existence and use of special preferences for those who are more privileged, such as the children of large donors or alumni.

Affirmative action has not only resulted in diversifying our campuses with more women and students of color, but it has also been part of a movement to diversify the curriculum. Affirmative action has helped to pave the way for underrepresented groups to attend college, to graduate and to write the histories of individuals who have been excluded or left out. Affirmative action has been part of including these voices, to explain why one group got stratified at one level as compared to another and to interpret why some groups were institutionalized at the lowest levels of the society.

There would be no need for affirmative action if every individual who wanted to attend college were granted that right.

In the meantime, we need to support efforts that consider race, ethnicity, gender, and economic status in admissions policies. Real unity among all those concerned will be brought about as we direct our energies to the policy-making arena and promote the idea that there is no contradiction in preserving affirmative action alongside “class- based” solutions.

Book – Organizing Lessons: Immigrant Attacks and Resistance co-edited by Jose Calderon and Victor Narro

UCLA Labor Center project director Victor Narro and Pitzer College professor José Calderón have released a new book as part of the “Taking Freedom” book series collaboration between SEIU’s Racial Justice Center, the MIT CoLab, and CUNY’s School of Labor and Urban Studies. Organizing Lessons: Immigrant Attacks and Resistance! features a collection of essays from immigrant rights activists, labor activists, and activist scholars working for immigrant and workers’ rights.

“The road to securing justice for immigrants and workers is a long and challenging one. Yet, the history of resistance movements is dense with stories of inspiring resilience, tenacity, and solidarity,” said Narro. “My hope for this book is to document and share these historic moments, so that we can better understand and utilize the power that the intersectional, multiracial immigrant rights movement has built.”

The book’s essays also articulate how immigration policy is related to larger questions of nation building, racialization, political participation, and social and economic inequality, alongside discussing the vibrant and increasingly intersectional organized resistance against repressive policies within the immigrant rights and labor movements.

“I am honored to co-author this anthology, as part of the Taking Freedom Series, which is aimed at sharing lessons of participatory research, learning, and organizing from the past and in the present,” said Calderón. “The readings in this anthology draw out lessons on the importance of building multiracial and intersectional solidarity in our immigrant rights, labor, and community-based movements: to fight alongside our communities against immigration and refugee policies that only focus on enforcement; to organize for policies that will immediately lead to permanent legalization with no expansion of temporary guest worker (bracero) programs and with labor law protections; and to cross borders in building international solidarity to turn around the neo-liberal systemic policies that have historically served only the interests of capital and multinational corporations.”

Included in the book are two articles authored by UCLA Labor Center staff: “The 2006 Immigrant Uprising: Origins and Future” by UCLA Labor Center director Kent Wong, project director Janna Shadduck-Hernández, and Narro, as well as “The Future of Work: Organize the Immigrant Workers” by Wong.

Organizing Lessons is available in digital format for free. To support classroom, workshop, and organizing discussions, a set of guiding questions accompanies each chapter.

Link of digital format of book for free:

On Supporting Immigrant/Refugee Rights

People rally outside the Supreme Court as oral arguments are heard in the case of President Trump’s decision to end the Obama-era, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA), Tuesday, Nov. 12, 2019, at the Supreme Court in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

“Building Multi-Racial Coalitions Against Trump’s Criminalization Policies”

| Jose Calderon |

The families who are coming here from Central America, Mexico, and Latin America overall are coming as a result of years of this country’s foreign policies toward those countries and the growing violence and poverty. These reasons include the economic inequalities that exist between the U. S. and Latin America, the uprooting of farmers and peasants as a result of trade agreements such as NAFTA that favor the subsidized multinational corporate interests in this country, and policies that result in the undercutting of staple crops such as beans and corn.

These policies have historically tended to separate immigrants coming to this country into political and economic refugees. Those coming from Cuba, for example, have been labeled as political refugees, as running from a country that this country has decided is persecuting them, and has welcomed them with speedy and immediate legalization status. This was also true for Vietnamese refugees who were also labeled as political refugees.

Those coming from Mexico or Central America are labeled as “economic refugees.” In practice, the U. S. during the Reagan administration continued to grant refugee status to immigrants from Southeast Asian and Eastern Europe while making it difficult for others fleeing places like Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador. Being a refugee then has not been a matter of personal choice, but of government decisions based on a combination of legal guidelines and political expediency. How one is classified, as either an economic or political refugee, depends on the relationship between the U. S. and the country of origin and the international context of the time. It is problematic because it is not an economic mode of incorporation but a political status, validated by an explicit decision of the U. S. government.

The immigrant and refugee families from Central America come from countries where U. S. companies have been using their cheap labor and resources historically. The immigrant and refugee families are also running from drug cartels who would have no success were it not for the demand of the consumers that are primarily located right here in the U. S. Many are hoping to be reunited with parents or relatives already living in America, and they cross the border without papers because there are virtually no legal ways for them to immigrate. Nor can their undocumented parents return home to get them.

The media primarily blames the immigrant and refugee families for leaving because of gang violence but there are deeper issues here. A lot of the gangs in Southern California were formed as part of the great migration from El Salvador when Ronald Reagan and the U. S. government in the 1980’s intervened in that civil war resulting in 75,000 deaths. Many were arrested and deported and, in El Salvador and other central American countries we saw the rise of death squads and the mass incarceration of gang members. After the war, there was a rise in gangs and, although the U. S. government has not played any role in developing programs to deal with this issue, it has been organizations such as that of Homies Unidos who have been in the forefront of organizing and reducing the incarceration of gang members. Similarly, the Central American country of Honduras, from where many recent refugee children and families are coming from, has had a long history of wars that have displaced thousands. More recently, in 2009, the U. S. supported a military coup in Honduras that resulted in the ouster of the democratically-elected government of Manuel Zelaya. Following the coup, there has been mayhem in the government with oppression of any groups that protest. The economy has been in dire stress and thousands of children and families have been thrown into the streets and, with nowhere else to go, have joined the thousands of refugees who have made their way to the U. S. Mexican border. This is also true for the thousands climbing on trains and leaving Guatemala, a country where the U. S. supported a military junta that killed thousands of indigenous people.

The media and politicians in this country bypass this history when they present the reasons why immigrant and refugee families are coming here and seeking asylum. As a result, we have had rabid racism and nativism displayed by angry mobs in places like Murrieta, California with cries that these families have no rights to be here and should be immediately deported.

This goes against the official reports by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which documents that almost 60 percent of the children and the families fleeing to the United States from Central America are legitimate asylum seekers.

It is only our efforts that can ensure that the asylum-seeking immigrant and refugee families stuck in places like Tijuana and those who are coming here are not removed through a non-judicial process but receive the opportunity for fair and full consideration of their legal claims with access to legal counsel. The cost of pushing these refugee and immigrant families back into dangerous or deadly situations is simply too high.

These children and families, under international law, are entitled to be classified as refugees from violence and war. They have the right, as refugees, to have legal assistance and to have their cases heard before a judge. Those who are found to be refugees from violence or persecution have the right to asylum. However, instead of the U.S. asylum system recognizing the unique forms of persecution that these immigrant and refugee families have faced in their host countries, they are being denied any opportunity to articulate their claims for asylum — they are simply detained for long periods of time in inadequate facilities with little regard for their best interests.

In recent years, we have learned that it is only our organizing work at the grass-roots that can ensure legislation that is truly just and that rewards, not criminalizes, immigrant families and refugees for their contributions. We have moved forward from the period in 2004-2006 when California Governor Pete Wilson used Proposition 187 to get re-elected, when the Sensenbrenner bill was advanced by the anti-immigrant conservative right, and when there was a cutting of bilingual education and affirmative action. It was not that long ago that many labor unions were anti-immigrant. Now, in a recent session of the CA legislature, it was unions that helped to pass Assembly Bill 450, requiring an employer to require proper court documents before allowing immigration agents access to the workplace or to employee information. Alongside this, it is important to recognize the role that Dream Act recipients played in moving policy at a federal level like no other organization has been able to do in recent years. It was Dream Act recipients, before the 2012 elections, that showed their capacities for exerting this political power by presenting 11,000 signatures, courageously leading protests in the streets, and holding a series of sit-ins across the country that, along with many community-based legal teams, led to Obama’s executive order granting “deferred action status” and implementing a Deferred Action Policy.

The best strategy that these combined forces have been able to advance has been one that has organized multi-racially at the local, state, and national levels. On the local level, in the city of Pomona, I have been part of coalitions that have included immigrant, labor (UFCW), student, faith-based, and community-based organizations. The Pomona Habla coalition, on a local level, was an example of a coalition that took a local issue about immigrant rights and connected it to policy changes statewide (while building support to change immigration policies nationally).

The coalition became a model for the passage of ordinances in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Baldwin Park allowing an unlicensed driver that permit an unlicensed driver to allow another licensed driver to allow another licensed driver to take custody of the vehicle rather than having it impounded. These statewide efforts led to the introduction of a bill by Assemblyman Gil Cedillo, and signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown, restricting local police from impounding cars at traffic checkpoint simply because a driver is unlicensed. This ultimately led to the passage of a bill allowing undocumented immigrants to obtain driver’s licenses.

In connecting the local to statewide efforts it is no accident why our political representatives have taken positions of “no ban and no wall,” supporting California as a sanctuary state, and vowing to protect the rights of our immigrant and targeted communities regardless of what oppressive policies Trump tries to force the states and cities to carry out. In recent years, it is the immigrant rights and worker movements who have pressured legislators in passing landmark pro–immigrant legislative policies such as: in-state tuition, driver’s licenses, new rules designed to limit deportations, state-funded healthcare for children, a new law to erase the word “alien” from California’s labor code, and the passage of SB-54, called the Sanctuary bill, which prohibits California officers from inquiring about a person’s immigration status and limits cooperation between California police officers and federal immigration agents. There are other bills in recent legislative session that have included measures to block the expansion of immigration detention centers, to protect undocumented immigrants from housing discrimination, and to stop unjust workplace raids.

The roots of these changes on the state level have their foundation in the organizing that is taking place at the grass-roots. On the local level, we have our coalitions that have been exemplary in the development of a partnership between the community-based Latino and Latina Roundtable organization, the Pomona Economic Opportunity Center, the Pomona Valley Chapter of the NAACP, the Inland Valley Immigrant Justice Coaltion, and others. In creating connections between the educational and immigrant rights needs of families, the partnership has implemented workshops for hundreds of students and parents in how to qualify for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, how to obtain a Matricula Consular card (an official identification document issued by the Mexican government), and (with a coalition with the Pomona Day Labor Center) workshops on how to obtain a California driver’s license. The partnership on K-12 and college pipeline issues has led to further action, including family summits and some parents who have gone with us to Sacramento to educate our representatives on bills to provide safe schools for immigrant children and to ban the use of public funds to aid federal agents in deportation actions, as well as other legislation to protect vulnerable students and advance educational equity. We have also been organizing by getting our members and others to understand the Real ID, after the California DMV began offering a compliant Real ID driver license or ID card as an option in order for its holders to be able to board a domestic flight or enter a federal facility as of October 1, 2020. Most of the undocumented community is not eligible to receive these documents, which exposes them to vigilantism, profiling, and persecution. We therefore have been calling on our communities to opt for a non-compliant I.D. or driver’s license for use in our daily life in California instead – and in this way our documentation will be the same as that of an undocumented person with a driver’s license, thus making the distinction between “compliant” and “non-compliant” documents less effective as a mechanism to isolate our undocumented community.

As part of these efforts, we have been organizing to defend the rights of our Central American families who have faced deportation with Trump’s actions to abolish the Temporary Protected Status program affecting many Central American families (some whom have been here for over twenty years) with children who have grown up in this country and are now attending school or college or have full-time jobs. When the Trump administration sought to deport over 400,000 immigrants with Temporary Protected Status (TPS), a coalition made up of organizations such as the National Day Labor Organizing Network, CARECEN-LA, and the National TPS Alliance led a campaign to defend the program. This multiracial coalition has been exemplary in organizing a grassroots network of over 70 TPS committees from across the country, in training new immigrant rights leaders, and in bringing two class-action TPS justice lawsuits that initially blocked Trump’s termination of TPS status for nearly half a million people from six countries: Haiti, El Salvador, Sudan, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Nepal. These efforts, while initially successful in achieving a one-year extension for all six countries covered by the two lawsuits, received a setback on October 12 when the Ninth U. S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the Trump administration and cleared the way for ending the protection of the 400,000 families covered under this program. In response, the coalition is embarking on a “Road to Justice” bus tour exposing how Trump’s TPS terminations were motivated by racism, going to 54 cities in 32 states, and ending with advocacy actions and meetings with congressional legislators in Washington, D.C.

Instead of supporting billions for surveillance technology, including unmanned drones and military-grade radar and billions toward the construction of a double-layer fence, our coalitions have continued to fight to stop the deportations of our undocumented brothers and sisters, who are not hard-core criminals, but whose only crimes are to work to feed their families here and abroad!

We continue to point out through forums and our research that the focus of this administration on enforcement and against a speedy process goes against the many studies that show how much undocumented immigrants would stimulate the economy if they were allowed legalization as quickly as possible. According to the American Progress organization, a speedier legalization would result in: an additional $1.4 trillion to the Gross National Product between the present and 2022; resident workers benefitting with an additional $791 billion in personal income; and the economy creating an average of an additional 203,000 jobs per year. Within five years of their legalization, undocumented immigrant workers would be earning 25% more than they are earning resulting in an additional tax revenue of $184 billion (with $116 billion to the federal government and $68 billion to state and local governments). Overall these statistics sustain the argument that the sooner asylum and legalization can happen, the more the significant gains for all working people and the greater the gains for the U.S. economy.

A progressive immigration policy will take fighting for supporting the allocation of funds for processing and not for enforcement — to take the millions being proposed for more fence and more border officers and use it for a more efficient means of doing away with a backlog of thousands waiting in line for legalization. It needs to include additional resources to allow for hearings that ensure the rights and interests of the children and families in all proceedings, so that they can be released as quickly as possible from Border Patrol facilities that are inadequate.

Beyond the short-term need to ensure protection of rights and safe environments for our immigrant and refugee families, it is important to deal with the reality of conditions that are occurring in Latin American countries. What is true is the reality that immigrant workers will remain in or return to their homeland when the economy in these countries improves. If the U. S. federal government was really interested in doing something about immigration long-term, it would work to strengthen the sending countries’ economies. There is no reason why the U.S. could not develop bilateral job-creating approaches in key immigrant-sending areas. What is needed now and long-term is moving away from policies that merely focus on an enforcement that racially profiles our communities to policies that will speed-up the process to legalization, and advance a commitment to enhanced funding streams for economic development in the immigrant-sending countries (such as El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras).

It was refreshing after Trump’s announcement of non-support for DACA to see how people from all backgrounds walked out of schools and jobs to protest in support. Our support for the DACA program has been further bolstered by a study that just came out from Professor Roberto Gonzalez, of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, how DACA has benefited over 800,000 of our young immigrants, contributed to the nation’s workforce, and added billions of dollars to the economy. This study comes at a time when the Supreme Court opposed the Trump Administration’s policies to terminate DACA (sending the decision back to the Department of Homeland Security) and brings forward the significance of the November presidential elections in deciding its future.

With this administration’s attacks in opposing DACA and TPS, it is more important than ever to continue organizing marches and protests by our individual organizations alongside building multi-racial coalitions who are collectively carrying out voter turn-out efforts to ensure the election of representatives who truly represent the interests and issues of our communities; fighting alongside our communities against immigration and refugee policies that only focus on enforcement; and fighting for policies that will immediately lead to permanent residency and citizenship for our immigrant and refugee families with no expansion of temporary guest worker (bracero) programs and with labor law protections.